One editorial and two blogs by the New York Times personality. His points out the imbalance between consumption and investment, and also talks about the Lewis Point - the end of surplus labor (perhaps brought about by malinvestment).

First the editorial:

Yet the signs are now unmistakable: China is in big trouble. We’re not talking about some minor setback along the way, but something more fundamental. The country’s whole way of doing business, the economic system that has driven three decades of incredible growth, has reached its limits. You could say that the Chinese model is about to hit its Great Wall, and the only question now is just how bad the crash will be.

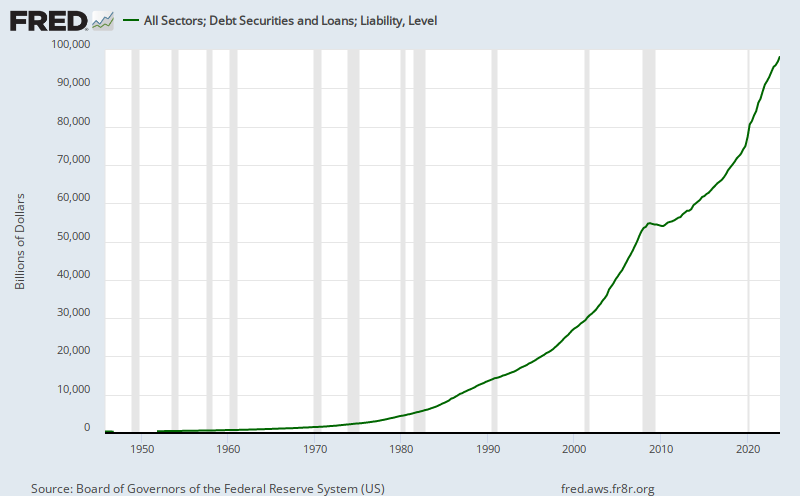

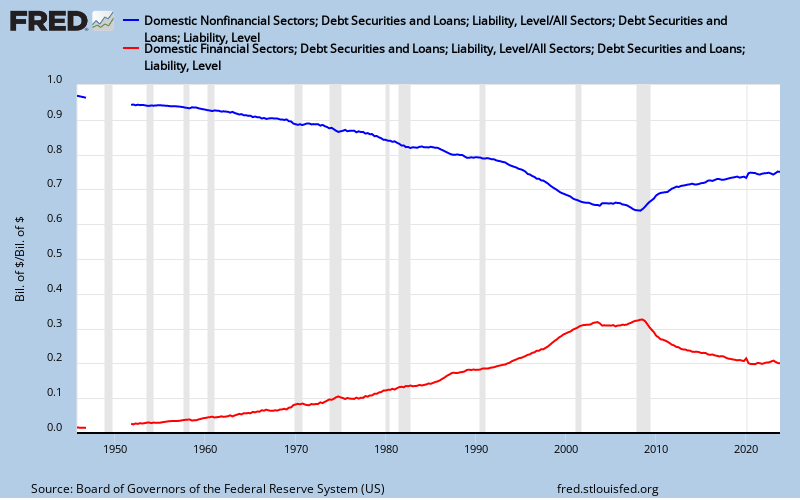

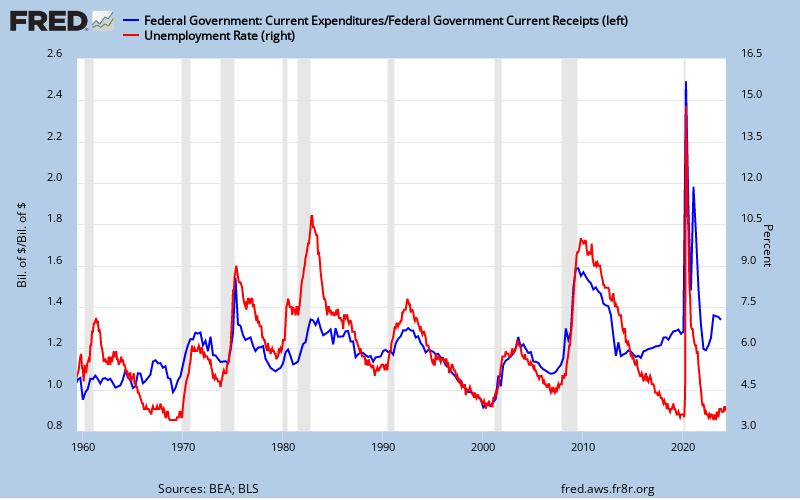

Start with the data, unreliable as they may be. What immediately jumps out at you when you compare China with almost any other economy, aside from its rapid growth, is the lopsided balance between consumption and investment. All successful economies devote part of their current income to investment rather than consumption, so as to expand their future ability to consume. China, however, seems to invest only to expand its future ability to invest even more. America, admittedly on the high side, devotes 70 percent of its gross domestic product to consumption; for China, the number is only half that high, while almost half of G.D.P. is invested.

...

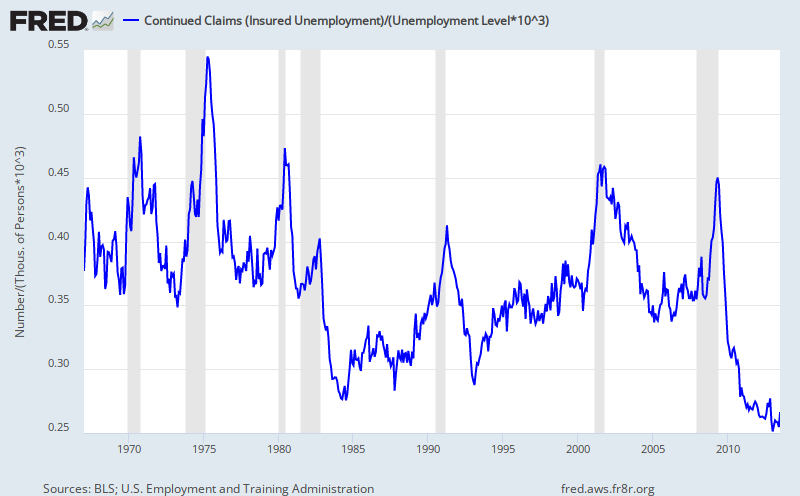

Now, however, China has hit the “Lewis point” — to put it crudely, it’s running out of surplus peasants.

Next, two blogs:

Also, my worries are that China doesn’t know how to slow down — that it’s a bicycle economy that falls over if it stops moving forward.

And of course I’ve argued that running out of peasants creates a wall.

So, the Chinese Ponzi bicycle is running into a brick wall. Also, the fascist octopus has sung its swan song.

Still not sure I’m living up to the world’s worst sentence, however.

Commodity prices are a potentially bigger story. China is a major consumer of raw materials — for example, about 11 percent of world oil consumption. And because the supply and demand of commodities tend to be relatively unresponsive to prices in the short run, a sharp drop in Chinese demand could lead to sharp falls in commodity prices. So the Ponzi bicycle shock could be a bigger deal for countries that sell raw materials, whether they sell to China or not, than it is to China exporters.